Reactivity in Chemistry

Radical Reactions

RR4. Radical Initiation: Single Electron Transfer

We saw in the section on redox reactions that single electrons can be transferred from one species to another. Because one electron is transferred at a time, radicals can be initiated this way.

Metals that are high in the activity series, such as lithium or sodium, can easily donate their valence electrons to organic compounds. As a result, those organic compounds become radicals.

Li → Li+ + e-

Na → Na+ + e-

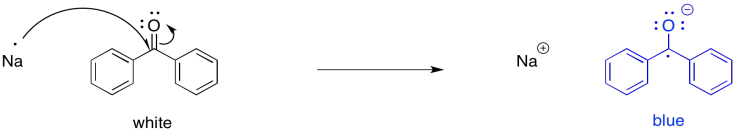

The possibility for this reaction is most easily illustrated with an example from carbonyl chemistry. Carbonyls are electrophiles. The electrophilic carbon normally accepts a pair of electrons from a nucleophilic donor. However, a single electron could be thought of as a nucleophile, too.

For example, if benzophenone is dissolved in an unreactive solvent, such as ether, over a few pieces of sodium, the sodium can transfer an electron to the carbonyl. The interesting thing about this reaction is that, although benzophenone is a white (or colourless) compound and ether is a colourless liquid, the ether solution turns deep blue after a couple of hours. Benzophenone radical anion is a deep blue colour.

Figure RR4.1. Initiation of a radical anion by single electron transfer.

Benzophenone radical has long played an important role in research labs. For many years, sodium has been used as a drying agent for organic solvents. Because of the well-known propensity of sodium to react with water, any traces of water in a flask of ether are destroyed. They are converted to sodium hydroxide and hydrogen gas. However, in the absence of water -- that is, if the sodium has already done its job -- the sodium can transfer electrons to benzophenone in solution, producing a blue colour. Benzophenone thus works as an indicator to let researchers know that the solvent is dry.

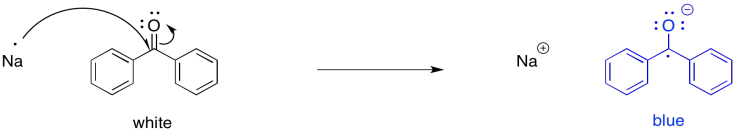

After a few more hours, the colour changes once more to a deep purple. That's because a second electron gets transferred to the benzophenone radical, forming benzophenone dianion. That's when you know the solvent is really, really dry. However, all of this has to be done under a nitrogen atmosphere, or else the benzophenone radical anion undergoes additional reaction with oxygen, producing yellow schmutz all over the flask instead of the beautiful purple colour. This drying method also works with benzene or toluene, or with a little modification, saturated hydrocarbons such as pentane. It doesn't work with many other solvents, which might instead react directly with the sodium.

Figure RR4.2. A second single electron transfer to make a dianion.

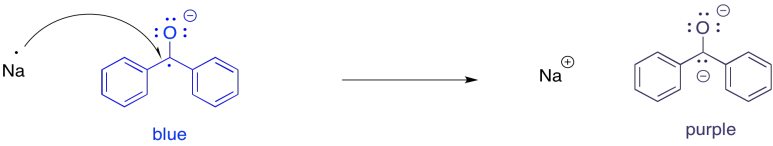

But what would happen if, at this point, we carefully introduced some protons? Maybe it is in the form of an acid, either strong (HCl) or very weak (NH4Cl). The benzophenone dianion would surely get protonated, and since it is a dianion it would get protonated twice.

Figure RR4.3. Protonation of a dianion.

The overall result is a reduction of the benzophenone to the corresponding alcohol, 1,1-diphenylmethanol. It would be just like we had added sodium borohydride, a source of nucleophilic hydride (that's a proton plus two electrons) and then did an acid workup (adding a second proton). In this case, we have just added the components (two electrons, two protons) in a different order.

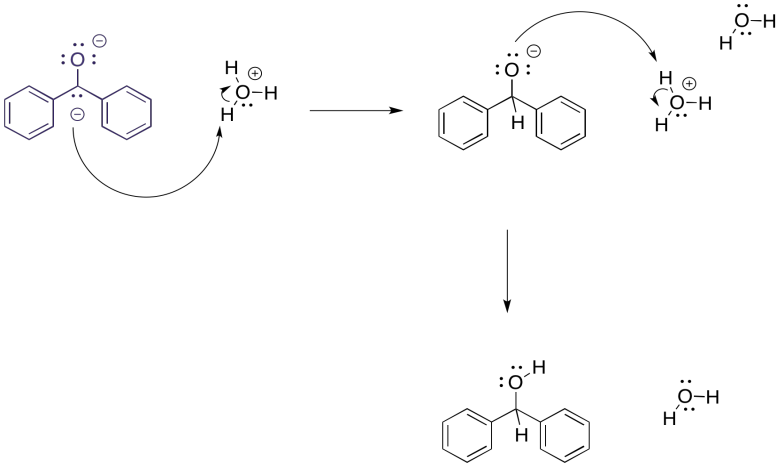

Furthermore, this method of reducing things isn't really limited to carbonyls. Alkynes and aromatics are also susceptible to reduction to the radical anion or dianion, although the reaction is more commonly performed using lithium.

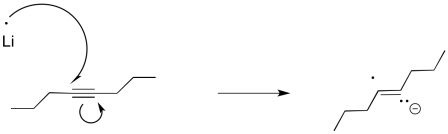

Figure RR4.4. A single electron transfer to an alkyne.

We can imagine a similar process of protonation occurring to get an alkene. It looks a little like an alkyne reduction, but instead of using H2 as the source of hydrogen atoms, we have used an alkali metal as the source of the electrons and an alcohol as the source of protons.

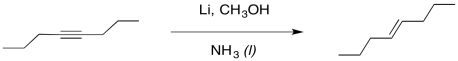

Figure RR4.5. Dissolving metal reduction of an alkyne.

Interestingly, these latter reactions are stereospecific. The sites of the anions (and subsequent protonations) are as far apart as possible. That means that the anions are found trans- to each other in the alkenyl anion. As a result, the trans alkene always results from lithium reduction. This reaction is complementary to hydrogenation with Lindlar's catalyst, which always results is cis alkenes.

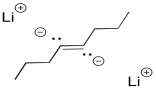

Figure RR4.6. A poddible dianion intermediate in a dissolving metal reduction.

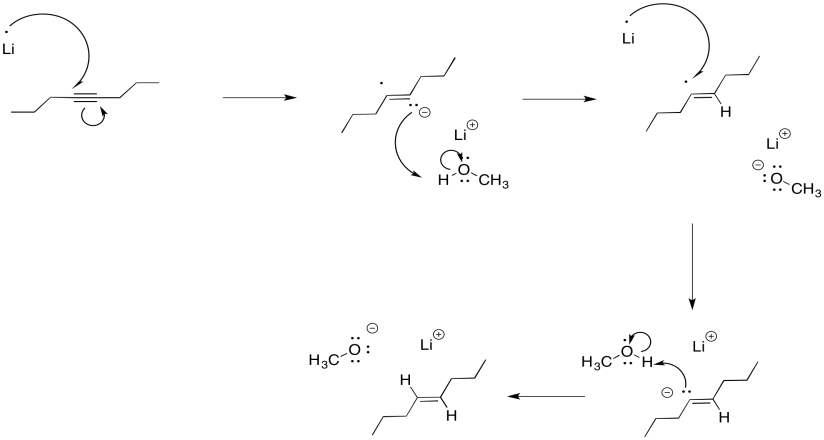

It may be surprising that the dianion is not required in order to get this "keep-the-negative-charges-far-apart" selectivity. Normally, these reductions are conducted in liquid ammonia, often with a little bit of alcohol added. Under those conditions, the initial radical anion is protonated before the second electron donation. The dianion never actually forms, yet the selectivity is still the same. Repulsion between the lone pair and the radical are enough to account for the stereoselectivity.

Figure RR4.7. A dissolving metal reduction in the presence of a proton donor.

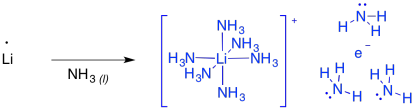

These reactions are sometimes called "dissolving metal reductions" because the lithium metal dissolves in the liquid ammonia. In ammonia and some amines, the metal actually undergoes ionization to produce Li+ and e-. This "salt" is called "lithium electride" and it produces a bright blue colour. It is really a coordination complex, with a hexaammine lithium cation and an ammonia-solvated electron. Furthermore, the solution is paramegnetic and highly conducting, because of all of those unpaired electrons floating around on their own.

Figure RR4.8. Formation of lithium electride.

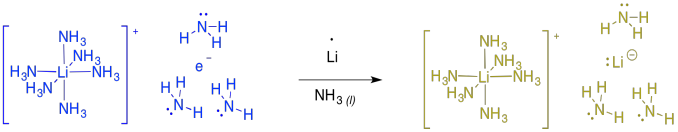

If you keep adding more and more lithium to the ammonia, at some point the solution becomes diamagnetic and turns gold in colour. At this point, the evidence suggests formation of "lithium lithide", or Li+ Li-. The same thing happens with other alkali metals, such as sodium or potassium, producing bronze-coloured sodium sodide or potassium potasside.

Figure RR4.9. Formation of lithium lithide.

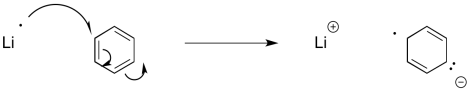

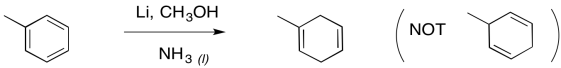

Similar reactions occur with aromatic systems. These reactions are called "Birch reductions". Because of the same electron-electron repulsion problem encountered in alkyne reduction, Birch reductions always result in the radical / anions positioning themselves at the 1,4-positions in the benzene ring.

Figure RR4.10. Initiation of a radical anion by single electron transfer to benzene.

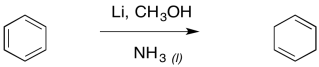

The result is a cyclohexa-1,4-diene. Just like with the alkyne reduction, the Birch reduction is usually performed with a small amount of alcohol in solution.

Figure RR4.11. A Birch reduction is a dissolving metal reduction of a benzene.

Furthermore, the remaining double bonds from a Birch reduction are in the more substituted positions; that's understandable in terms of the trend of alkene stability, in which more substituted double bonds are more stable.

Figure RR4.12. Birch reduction is regioselective.

Problem RR4.1.

Illustrate the products of single electron transfer from lithium to the following compounds

a) 2-hexyne, CH3CC(CH2)2CH3 b) 2-butanone, CH3COC2H5 c) allyl bromide, CH2CHCH2Br

Problem RR4.2.

Single electron transfer is much more difficult to a carboxylate anion than to an aldehyde or ketone. Explain why.

Problem RR4.3.

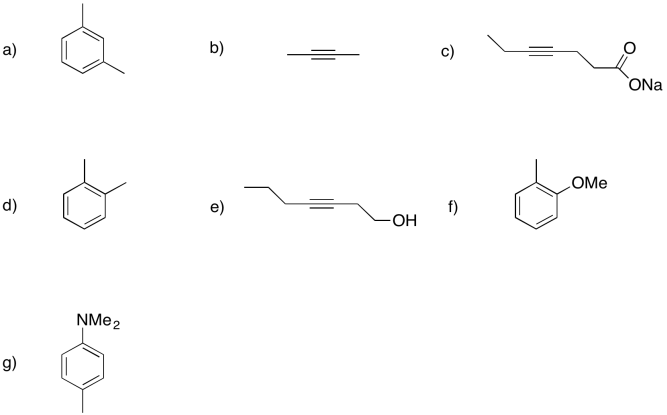

Show the products of dissolving metal or Birch reductions in the following cases.

Problem RR4.4.

Show the mechanism for the Birch reduction of m-xylene (m-dimethylbenzene) with lithium and methanol in liquid ammonia.

This site is written and maintained by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with contributions from other authors as noted. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation: