CO9. What is a Nucleophile?

Lots of things can be nucleophiles. In principle, a nucleophile only needs a lone pair. However, some nucleophiles are better than others.

You already know something about nucleophiles if you know something about acidity and basicity. Nucleophiles are really Lewis bases. Some of the factors that account for basicity also account for nucleophilicity.

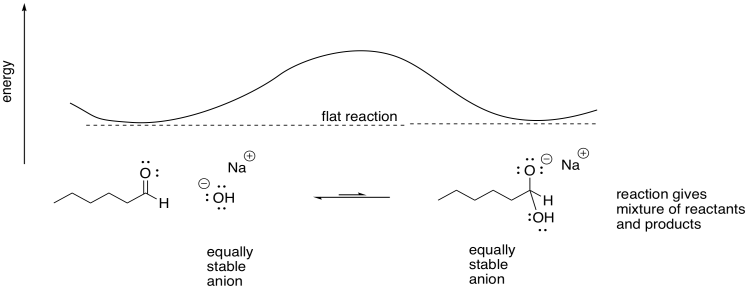

Halides are not very good nucleophiles for carbonyls. The negative charge on a halide is pretty stable, either because of electronegativity or polarizability. If a halide donates to a carbonyl, producing an oxygen anion, the reaction is uphill.

- Halides are poor nucleophiles because a negative charge is more stable on a halogen than an oxygen.

Hydroxide and alkoxide anions (such as CH3O-) are more reactive than halides. They are better nucleophiles. The sulfur analogues are similarly good nucleophiles (such as CH3S-). In addition, water, alcohols and thiols are nucleophilic, because they all have lone pairs that could be donated to an electrophile.

- Oxygen anions could be better nucelophiles than halides because the negative charge formed in addition is just as stable as the negative charge on the nucleophile.

Nitrogen also has a lone pair in most compounds. That means amines are good nucleophiles, too.

- Oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen don't have to be anions to be nucleophiles: alcohols, thiols, and amines have nucleophilic lone pairs even when they are neutral.

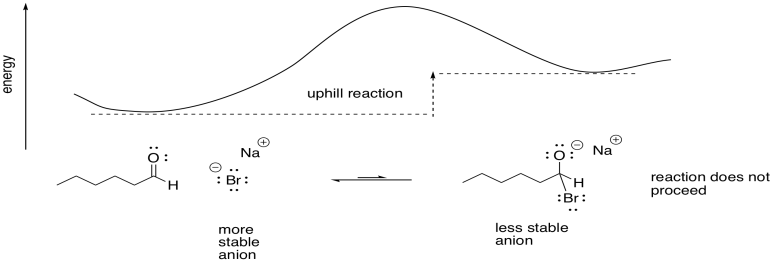

Carbon does not normally have a lone pair, unless it is a carbanion. Carbanions are usually not very stable. As a result, they are not very common, except for cyanide (CN-) and acetylides (RCC-, in which R is a hydrogen or an alkyl group). However, when carbon does have a lone pair (and a negative charge), it is a good nucleophile. Because carbon is less electronegative than other elements with lone pairs, it is able to donate its lone pair easily.

Carbon nucleophiles add to carbonyls because that less stable carbon anion is traded for a more stable alkoxide anion. The reaction is downhill energetically.

Figure CO9.1. A nucleophilic addition that is energetically downhill.

Problem CO9.1.

Carbanions such as CH3- (methyl anion) are very unstable and highly reactive. Explain why the following anions are more stable than a methyl anion.

- Acetylide, HCC-

- cyanide, CN-

Other nucleophiles, such as halides, do not proceed. They are going uphill, from a more stable halide ion to a less stable alkoxide ion.

Figure CO9.2. A nucleophilic addition that is energetically uphill.

If the nucleophilic atom were an oxygen anion, there might be an equilibrium. The reaction would be neither uphill nor downhill. It would result in a mixture of the original reactants and the new products.

Figure CO9.3. A nucleophilic addition that is energetically neutral.

Problem CO9.2.

Nucleophilicity is the degree of attraction of a nucleophile to a positive charge (or partial positive charge). It is related to basicity. Choose the most nucleophilic item from each of the following pairs, and explain your answer.

- CH3OK or CH3OH

- CH3OH or CH3NH2

- NaCN or NaCCH

- c-C6H11ONa or c-C6H5ONa (c- in this case means "cyclo")

Problem CO9.3.

Carbonyl compounds such as aldehydes and ketones contain a very slightly acidic hydrogen next to the carbonyl. Some nucleophiles are basic enough to remove that proton instead of donating to the carbonyl. Show why the resulting anion is stable, using cyclopentanone as an example.

Problem CO9.4.

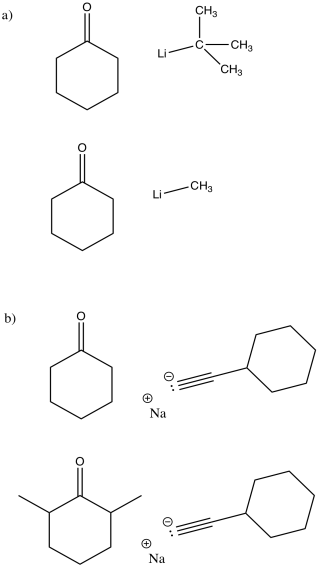

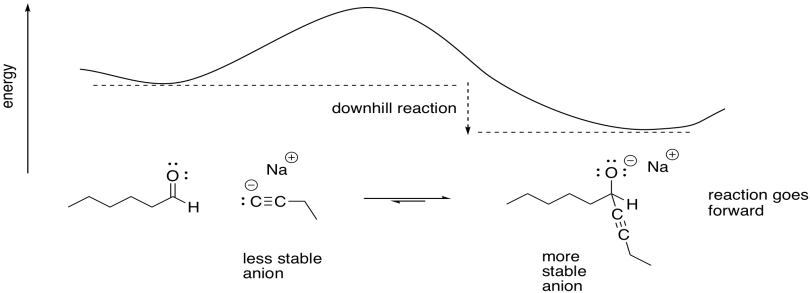

Accidental deprotonation (proton removal) alpha to a carbonyl (one carbon away from the carbonyl) can occur when a nucleophile is added to a ketone. One reason the proton might be taken instead is if the carbonyl is too crowded for the nucleophile to reach.

In the following cases, explain which nucleophile is more likely to add to the carbonyl in cyclohexanone and which is more likely to deprotonate it.