CO7. The Mechanism of Carbonyl Addition: Step One

Carbonyls act most importantly as electrophiles. They attract a pair of electrons from a nucleophile. When that happens, a bond forms between the nucleophile and the carbonyl carbon.

At the same time, the carbon-oxygen bond breaks. We think of that as a consequence of donating a pair of electrons into the LUMO of the carbonyl. The LUMO on the carbonyl is the C-O pi antibonding orbital. When that orbital is populated, there is no longer a net lowering in energy due to the pi interaction between the carbon and oxygen. The pi bond breaks. The electron pair from the pi bond goes to the oxygen, the more electronegative of the two atoms in the original bond. It becomes a lone pair.

- The first step in addition to a carbonyl involves formation of a bond between the nucleophile and the carbonyl carbon.

- The first step also involves breaking the π bond between the carbonyl carbon and oxygen.

- The pair of electrons in this π bond becomes a lone pair on oxygen.

After the pi bond breaks, the reaction reaches a branching point or decision point. The reaction may go forwards or backwards. In other words, this reaction can occur in equilibrium.

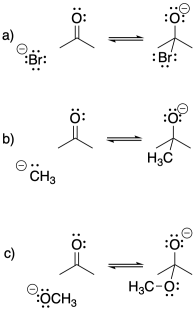

Figure CO7.1. Nucleophilic additions can be reversible.

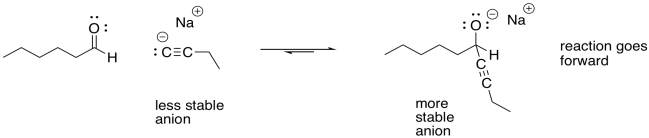

To go backwards, the reaction simply slides into reverse. A lone pair on the oxygen donates to the carbon, forming a pi bond again, and pushes the nucleophile off. Whether the reaction ends up going forward or sliding backward depends partly on the relative stability of those two ends of the reaction. That's often very difficult to assess qualitatively, because there are too many factors involved. However, one factor that plays a role is charge stability. Because an "O minus" or alkoxide is produced in this reaction, if the original nucleophile was a more reactive ion than an alkoxide, the reaction probably goes to the right.

For that reason, many of the best nucleophiles for these reactions involve carbon anions or hydrogen anions. Those anions are less stable than oxygen anions.

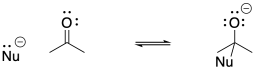

Figure CO7.2. Anion stability is a factor in the equilibrium shifting right.

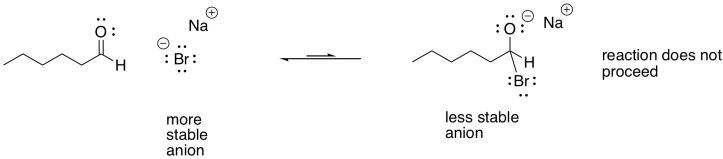

If the nucleophile were less reactive than alkoxide, the reaction could easily go to the left again. For that reason, stable halide ions (fluorides, chlorides, bromides, iodides) are not very good nucleophiles for these reactions. They have lone pairs, they even have negative charges, but the anion that would be produced would generally be less stable than the original halide ion.

Figure CO7.3. Anion stability is a factor in the equilibrium shifting left.

Problem CO7.1.

Provide curved arrows and predict the direction of equilibrium in the following cases.

-

More reactive nuceophiles push the equilibrium to the right

-

Less reactive nucleophiles do not push the reaction to the right; the reaction remains on the left

What happens after the initial equilibrium? In most cases, the alkoxide that is formed will become protonated. It will pick up a proton to become an alcohol. The source of the proton may be an acid, deliberately added to provide the H+. Alternatively, it may just be a very slightly acidic molecule such as water or another alcohol.